How to Build a Business Capability Map for Strategic Planning

Reading Time:

Lead the pack with the latest in strategic L&D every month— straight to your inbox.

SubscribeStrategy without execution is just wishful thinking.

That’s why so many organizations struggle to close the gap between CEO priorities and day-to-day operations. Everyone’s working hard, but often on different things: HR talks roles, IT talks systems, marketing talks customers. A business capability map cuts through the noise. It shows—visually and simply—what the business must be able to do to deliver on strategy, creating a common language that every function can act on.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through how to define specific business capabilities, the best way to structure them, and the pitfalls to avoid when creating a business capability map.

What is a business capability map?

A business capability map (or model) is a visual display of the structure and hierarchy of an organization’s defined capabilities.

- A business capability is what a company must do to generate value.

- Combined, business capabilities define the systems, processes, and outcomes that let the company achieve its mission.

For example, in a retail bank, top-level capabilities might include Customer Onboarding, Risk Management, and Product Development. Each of these decomposes into sub-capabilities, like identity verification, credit assessment, and product design.

Business capability map vs capability framework

These are complementary tools with some differences.

- A business capability map shows the hierarchy of capabilities, but does not provide any nuance beyond naming a capability and relaying its hierarchical position.

- A capability framework goes further, defining capabilities, the proficiency levels for each, and how they’re applied across roles. Frameworks become the foundation for performance reviews, capability assessments, job design, workforce planning, and learning strategies.

Together, they’re complementary. The map gives leaders the “what,” while the framework gives HR, L&D, and managers the “how well” and “to what standard.”

Business capability modeling is another term thrown around; truthfully, it describes the first step of building a business capability map, rather than being an entirely different process.

The importance of business capability mapping

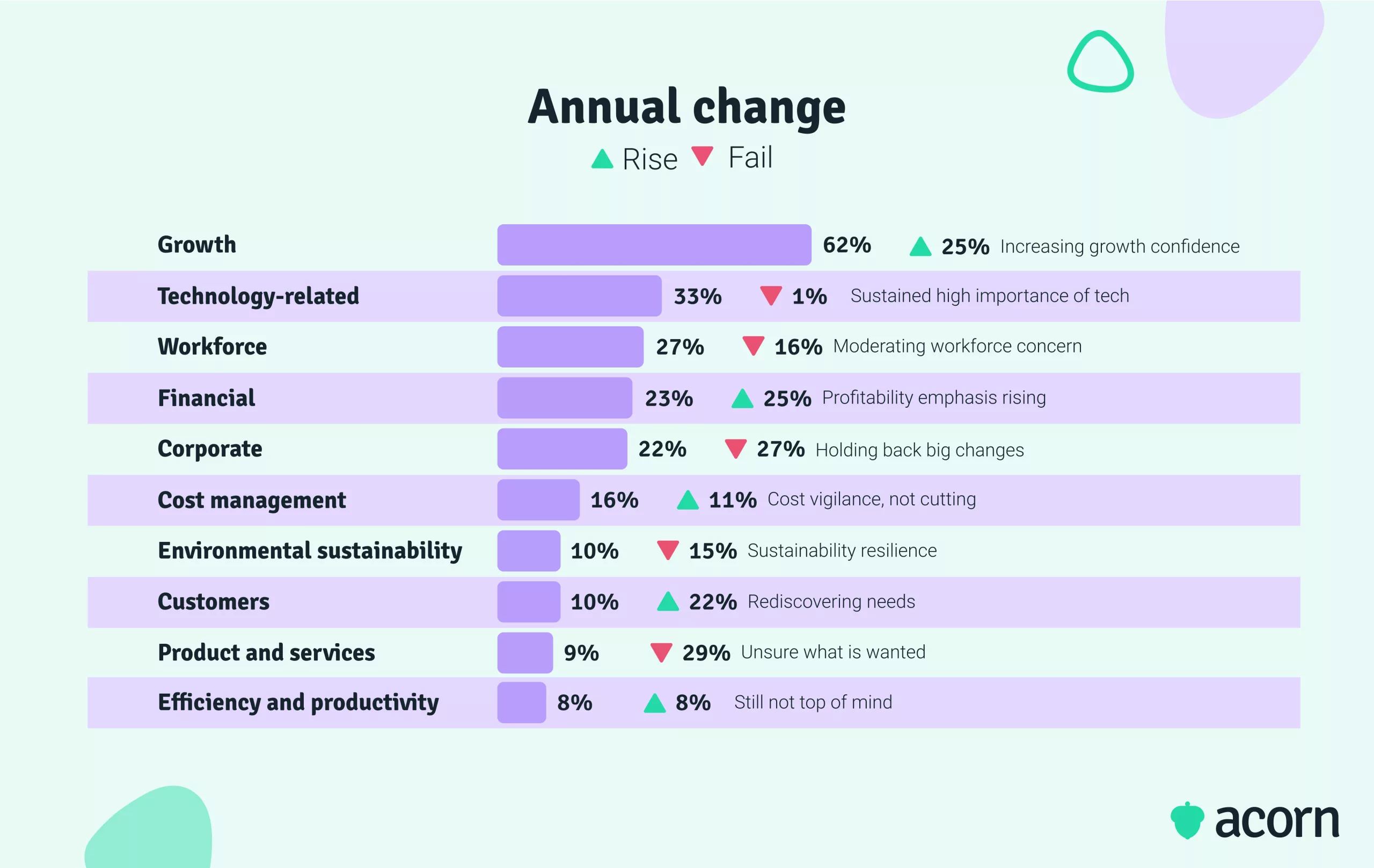

Strategy and execution aren’t always as closely related as you think. Emerging technology, shifting customer expectations, and workforce instability all pull priorities in different directions.

When trying to cover all these ends, organizations can start speaking different languages internally. HR might talk about internal mobility, while marketing focuses on changing strategic objectives, and IT wants to invest in new enterprise architects. No one sees eye-to-eye on how things are running, what’s high priority, and what has the biggest business impact, which means no one’s really acting on the CEO’s priorities, and therefore likely not acting on the business mission.

A capability map closes that gap. It creates a shared source of truth grounded in CEO priorities, making clear which capabilities the business must excel at to deliver strategy.

Without a clear capability map, you risk:

- Misaligned processes and duplicated effort

- Functions optimizing for local performance at the expense of enterprise goals

- Overinvestment in low-priority capabilities

- Misinterpreting capability maturity, leading to erosion of core strengths

- Roles designed without reflecting the true work required

- Process improvements delayed because priorities aren’t visible.

The connecting thread here is performance. Most enterprise learning solutions aren’t designed for processes like mapping business capabilities to learning, and therefore, learning to business goals. This can make it tricky to sell capability mapping (and development, and the connection to performance improvements).

We see capabilities as the launchpad for a capability-led strategy. They’re what make performance conversations across the business intelligible. That’s also why we pioneered the performance learning management system (PLMS): it builds the bridge from capability maps to workforce development and performance outcomes. At scale, that gives you visibility of what capabilities are immediately available to you and what needs urgent development.

How do you define business capabilities?

Once more for those in the back: Business capabilities outline the systems, tools, processes, and objects that, when combined, drive business strategy and organizational success. They describe a what, not a how. (The organization’s mission is the why.)

For example:

- Performance management is a business capability.

- “Providing positive experiences” is not; that’s a goal.

- Setting performance targets is not; that’s a process.

Consider current and future state

Capabilities should describe not only what the business does today, but also what it must be able to do in three, five, or ten years.

To further narrow down what your business can do, consider:

- How you organize business units. The way your company is structured shapes the capabilities you recognize. For example, a centralized operations function may emphasize “process optimization” as a core capability, whereas a decentralized structure may highlight “regional delivery” instead.

- Key business processes. These are the repeatable flows of work that keep the organization running. If payroll, procurement, or product development are mission-critical processes, the associated capabilities should appear in your map.

- The tactical demands of the business. Think short- to mid-term pressures, like expansion into new markets, compliance with new regulations, or adopting new technology like AI. These demands often surface capabilities that may otherwise be overlooked.

- What informs senior business leaders’ decision-making. Capabilities are also about visibility. If executives regularly make calls based on data analytics, risk assessment, or customer insights, those decision-making enablers should be visible as core capabilities.

- The abilities, systems, structures, and processes you’ll need in the future. A map should point toward the horizon. For example, a manufacturer digitizing its supply chain needs to treat “digital supply chain management” as a future capability, even if maturity is currently low.

Think evergreen

Whilst allowing for future adaptability, capabilities should be as stable as possible, even when business processes, structures, or technologies shift. If a capability definition breaks every time a department reorganizes, it isn’t truly a capability—it’s a process or an activity.

Think of capabilities as the enduring “what” the business must do, not the “how.” Again:

- Organizational Development is a true capability. It exists whether HR is centralized or decentralized.

- Weekly Performance Check-ins is not a capability—it’s a process that might change with every restructure.

Using plain, widely recognizable language is key. Jargon or overly specific terms will date quickly and confuse stakeholders. If people across the business can’t read a capability name and immediately understand it, it probably isn’t evergreen enough.

Decompose cohesively

Once core capabilities are defined, break them down into sub-capabilities. The trap to avoid here is designing by department politics—e.g., each function carving out “their” piece of the map. That creates duplication and overlap.

Instead, use the MECE principle (mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive). Sub-capabilities should:

- Be distinct, without overlap

- Collectively cover all aspects of the parent capability.

For example, under Customer Management, sub-capabilities might include Acquisition, Retention, and Analytics. Together, they fully describe the work of managing customers without stepping on each other’s toes.

The right level of decomposition also depends on context:

- Large, complex organizations may need several layers (core, sub-capabilities, child capabilities).

- Smaller organizations can often stop at one or two layers, focusing on the capabilities that most directly impact strategy.

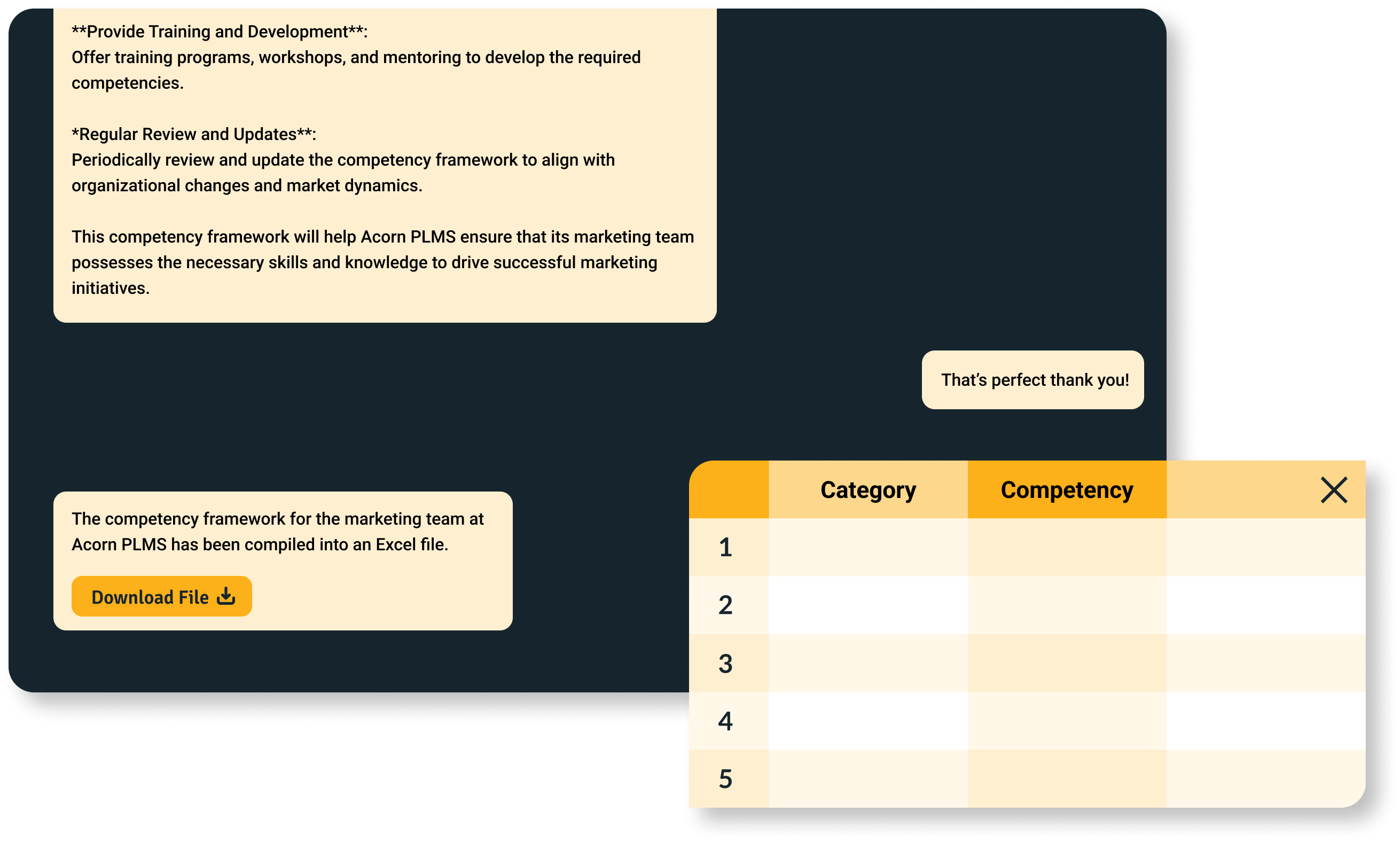

Yet to define your own capabilities? Get started in minutes (not months) with our Capability Assistant.

BUILD YOUR FRAMEWORKHow to create a business capability map

Defining business capabilities is just one step in creating a business capability model or map. (Who would have thought, right?)

There are a couple of approaches you could utilize to structure your map and outline capability hierarchies.

- Straw-based: Essentially, you’re starting from scratch and building your map based on internal data. Useful for differentiation, but demanding.

- Whiteboard: Borrow from industry models and tailor to your context.

- Top-down: Senior leaders define core capabilities, then decompose downward.

- Bottom-up: A more time-heavy approach, wherein business capabilities are defined at the task level. We wouldn’t recommend this one, since you’re trying to make the strategy fit the tasks.

However you choose to do business capability mapping, you’ll still follow the same core steps to structure and organize your map.

1. Organize capability sets

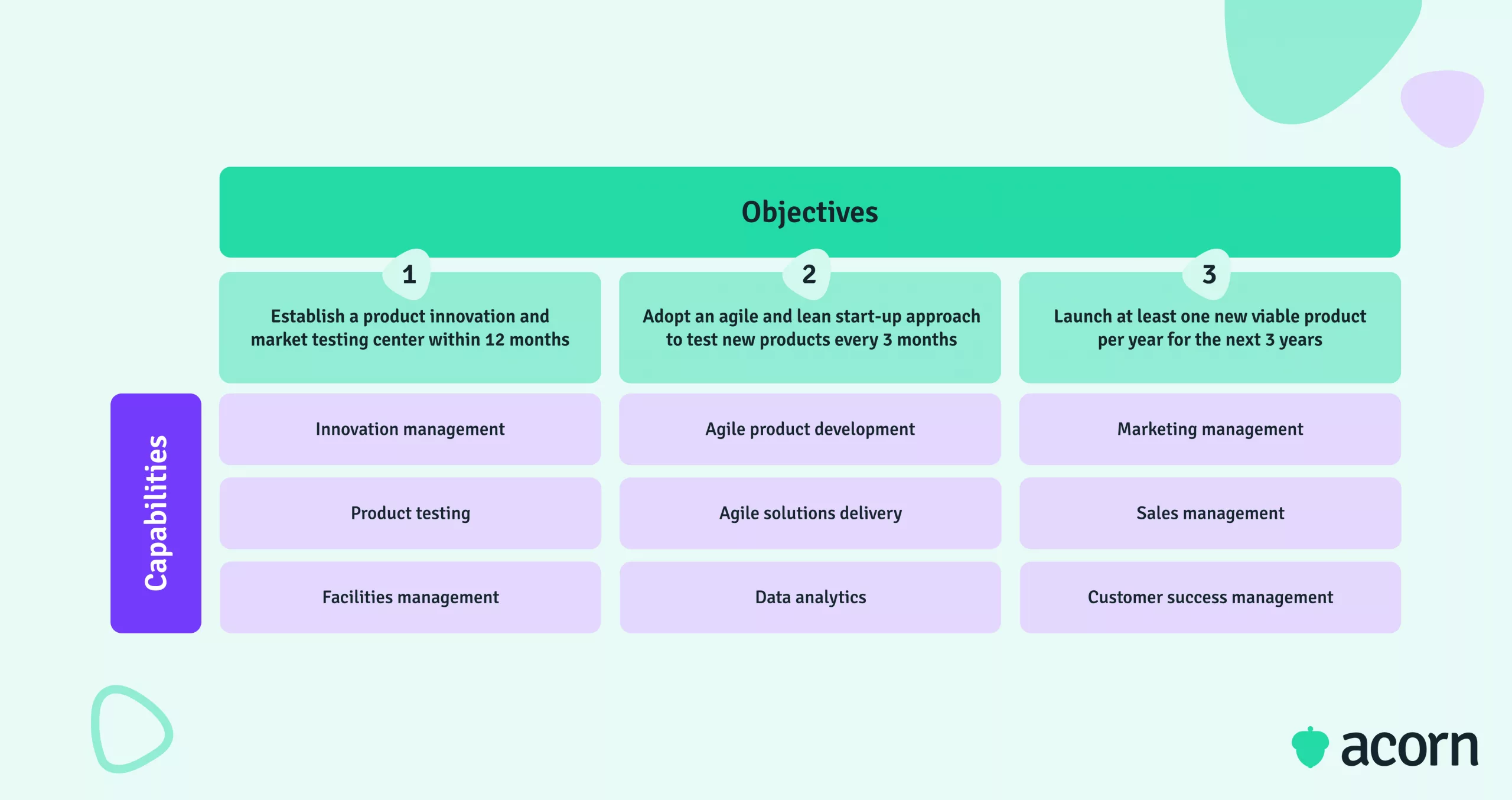

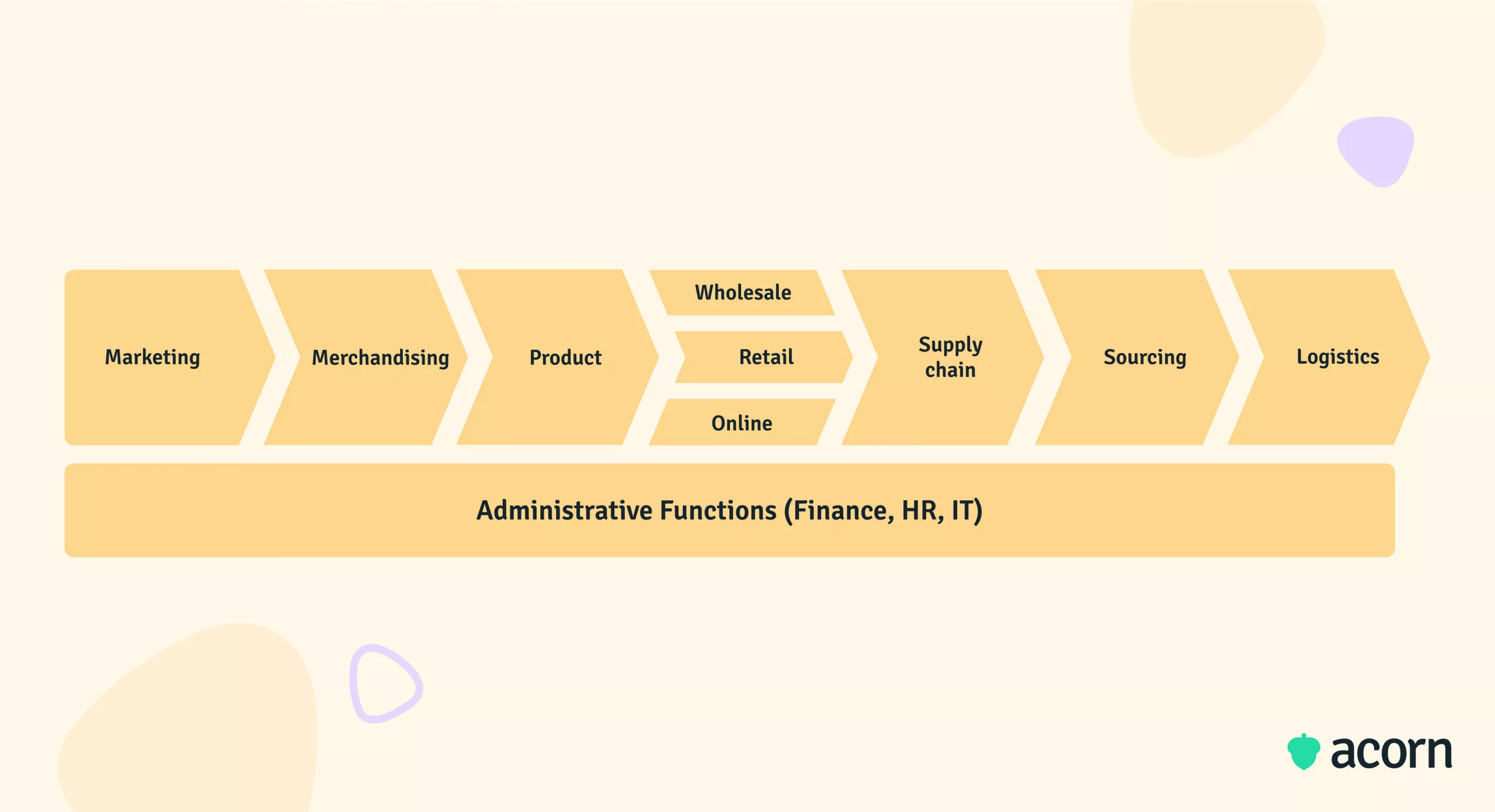

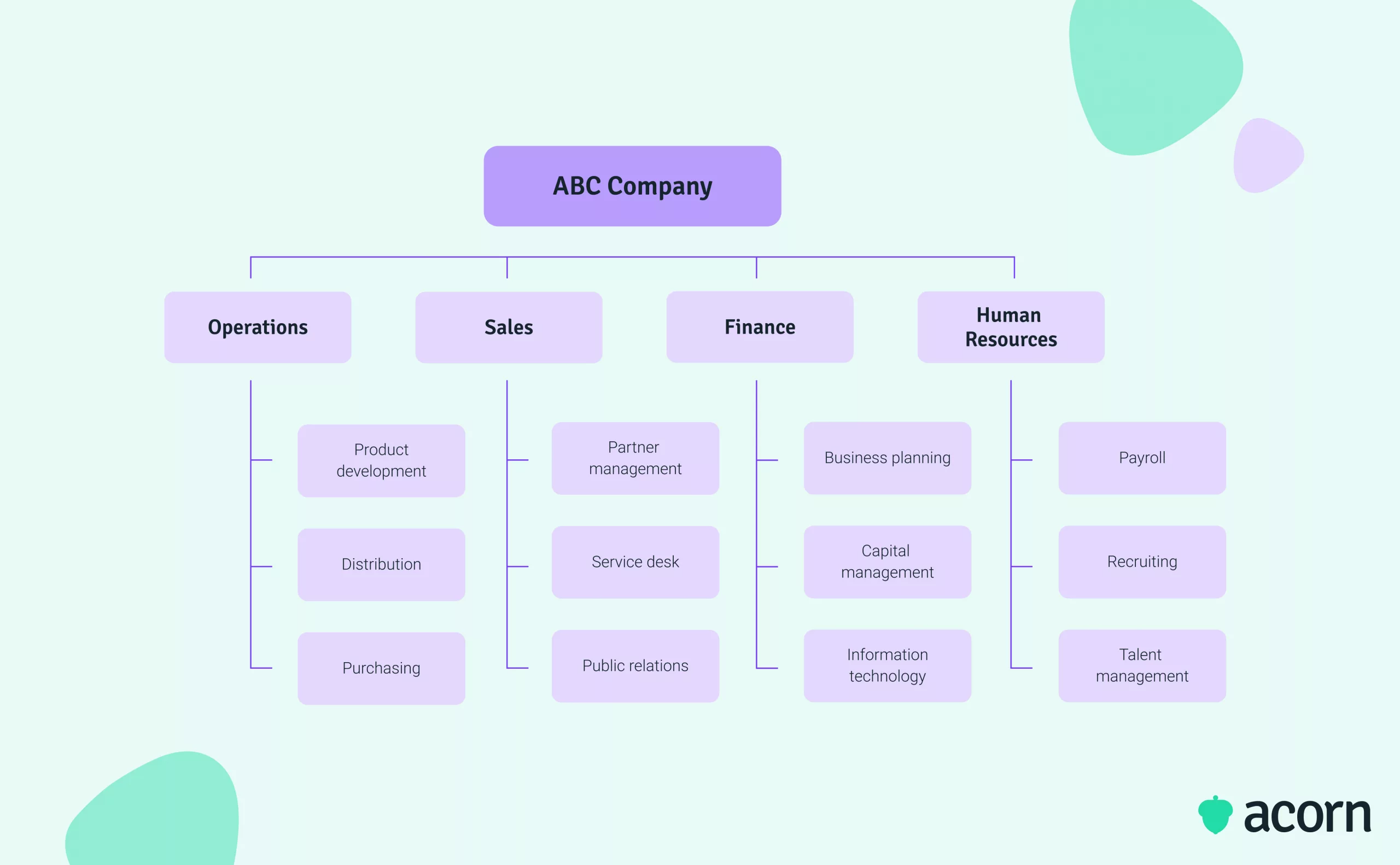

At the highest level, decide how you want to segment capabilities: by strategic objectives (e.g., growth, compliance, customer experience) or value chains (end-to-end activities like marketing → sales → delivery → support). The litmus test is whether everyone—from the CEO to frontline staff—can see how their work connects back to business priorities.

The former may look something like this.

While the latter could look closer to this.

Acorn’s Capability Library has been field-tested to strike this balance, starting with one set of core human capabilities, 33 functional and technical sets aligned to real job families, and additional sets dedicated to strategic priorities like leadership, digital literacy, and AI fluency. This kind of scaffolding prevents capability maps from collapsing under their own complexity—they need to be comprehensive enough to capture value chains, but lean enough to stay usable.

As a final note, the capabilities defined at this level must be as definitive as you can make them. Don’t get fancy with wording; keep it as simple as possible.

2. Define sub-capabilities

Sub-capabilities should describe the essential components of the parent capability, without duplication or overlap. For example, under “Customer Management” you might have “Acquisition”, “Retention”, and “Analytics”. Together, they fully define the work of managing customers.

Say we’re following the value chain or functional structure. Discussions with leaders would need to divine the non-negotiable elements of those chains.

You may choose to have fewer groups of business capabilities with more sub-capabilities.

You don’t necessarily need to have the same number of sub-capabilities under each core capability or capability group. The number of vital tasks will likely vary between stream, function, or objective.

Some helpful reminders when defining this initial layer of sub-capabilities include:

- Use nouns, not verbs (think what, not how)

- Note attributes of each capability if you don’t already have a framework in place

- Define what vital truly means. Not all tasks will equate to a capability; many will likely be grouped under the umbrella of one.

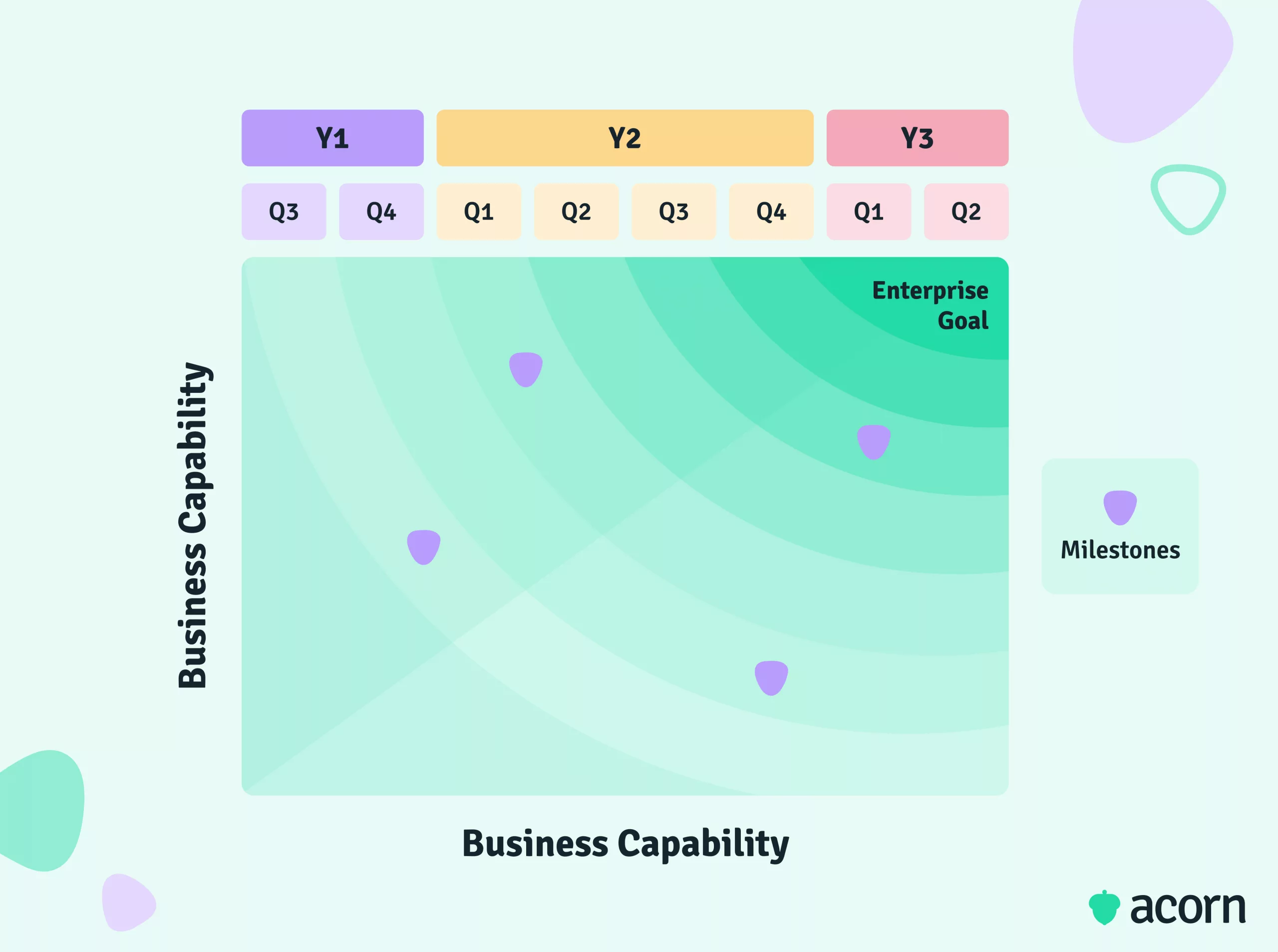

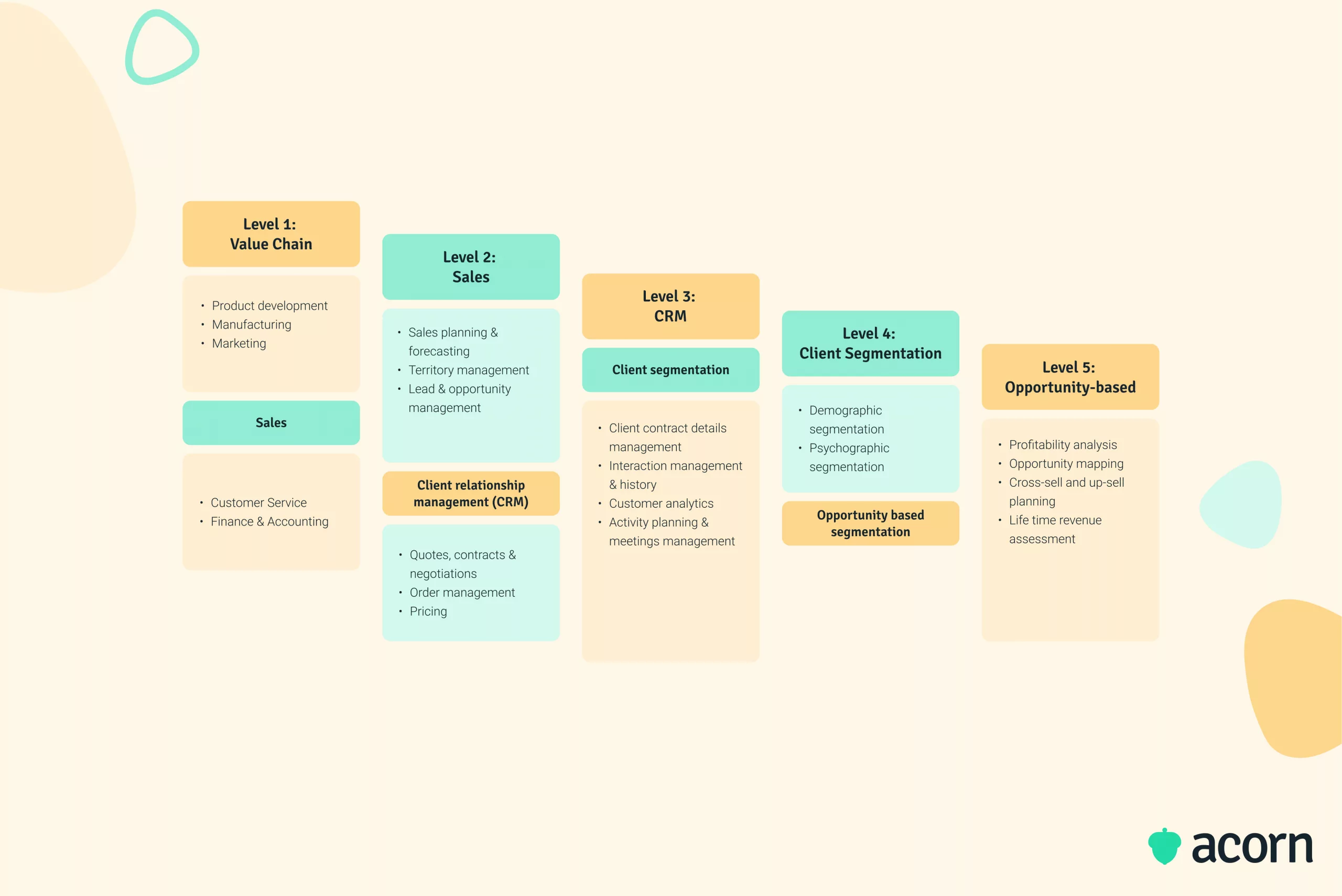

3. Decompose sub-capabilities

Sub-capabilities will have their own further decomposition. This level will likely be the most iterative, but it’ll also give you the most insight into activities like heatmapping and resource prioritization.

Large or complex organizations may need multiple levels: parent capabilities with children beneath them. The guiding rule is MECE: mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive. Each child capability should describe part of the parent, and together they should describe all of it, without overlap.

Take “Digital Marketing” as an example. At the sub-capability level, you might have “SEO,” “Paid Search,” “Social Media,” and “Analytics”. Each can be decomposed further if needed—”SEO” into “Technical SEO,” “Content Optimization,” and “Link Building”. The point isn’t to catalog every possible task, but to stop at the level where you can meaningfully assess maturity, prioritize investment, and design roles. Think in terms of processes, systems, functional requirements, and outcomes.

The pitfalls to avoid with business capability maps

Getting business capability mapping right isn’t always the easiest of tasks, though the outcome is a deceptively simplistic business tool.

Common pitfalls include:

- Treating mapping as an HR-only exercise rather than a cross-functional one.

- Overengineering detail too early instead of starting broad and refining.

- Using jargon or department-specific terms that confuse others.

- Forgetting MECE. Sub-capabilities must fully cover the parent without overlap.

- Leaving the map in a PDF with no integration into workforce tools or role design.

- Copying competitors instead of reflecting your unique value chain.

Key takeaways

Between business capability models, frameworks, and discovery tools, it can seem like there are a million things you need to enact a capability-led business strategy.

A business capability map is the starting point for a capability-led strategy.

- Maps create a shared language across functions, grounded in CEO priorities.

- They provide the structure for downstream processes like role design, workforce planning, and capability frameworks.

- The real value comes when maps are iterative—updated, tested, and linked to performance.

- Think of them not as static diagrams but as living tools that inform decisions across the enterprise.