How to Make Giving Performance Feedback Less Awkward and More Meaningful

Reading Time:

Lead the pack with the latest in strategic L&D every month— straight to your inbox.

SubscribeHow you say things is often more important than what you’re saying—or so the, well, saying goes.

In our humble opinion, this thinking causes some big issues in the old performance review. Managers want to give positive feedback to their teams, but often skirt around the point when talking about underperformance.

You can’t put the cart before the horse. You need to equip managers with the right language and tools to talk about performance to enable them to have meaningful and constructive performance conversations.

Why is it so hard to give meaningful performance feedback?

Performance feedback is inherently personal: It’s about somebody’s work ethic and effort. There’s no way around that, but that doesn’t mean feedback should be a personal attack.

Let us explain. Managers, especially those new to leadership, often lack confidence when assessing performance. That can be for a myriad of reasons. A 24-year-old manager feels they don’t have the authority to tell their 30-year-old team member they’re not performing to standard. A first-time leader has no experience running assessments. The newly promoted team lead can’t remember what someone was doing 7 months ago.

What all that does is make managers and employees alike feel bad.

- Employees feel like the goalposts are always moving, or like there are no goalposts to begin with (and therefore nothing to aim for or motivate them).

- Managers don’t feel like they’re doing right by their people or giving them real opportunities to grow in their careers.

- Employees feel like managers are making subjective judgment calls.

- Managers don’t feel like they’re developing their own leadership skills.

And those feelings have very real consequences (or Glassdoor and its peers wouldn’t exist). Managers account for at least 70% of variance in employee engagement. Globally, only 23% of employees consider themselves engaged at work, compared to 70% in best-practice organizations—i.e., those that actively try to increase employee engagement with committed managers.

But if you look closely enough, there’s another reason behind those reasons. They’re telling you they don’t feel like they have the authority to make an assessment? They haven’t been given the tools against which to measure performance. Never run an assessment before? Two-parter. 1. It’s not a structured process in their organization, and 2. They haven’t been trained to run one. Recency bias? No mechanism to record and reward performance throughout the year.

It’s hard to give meaningful feedback in performance reviews because they’re set up to fail. We’re not giving our managers the tools, language, or mechanisms to talk about performance, because we’re not talking the right language to begin with.

The case for a universal language for performance

A performance review process without regular development conversations is like capping a rotten tooth. It will just rot faster and more painfully.

Kim Scott, author of Radical Candor, talks about focusing on performance management vs performance development. Rating someone out of five every six-12 months is very different from having frequent conversations about how they’re going, what they can improve, and what they can do to improve.

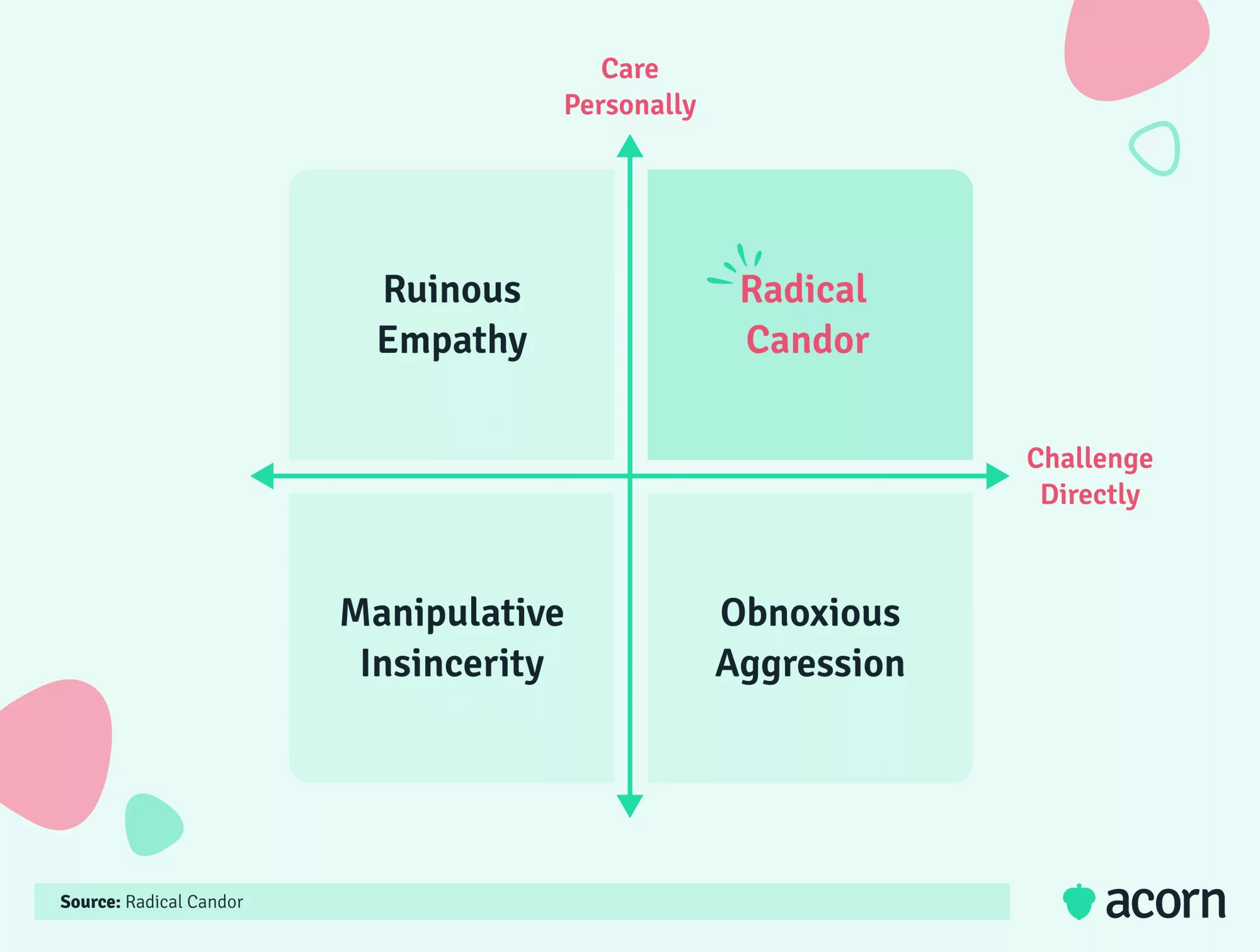

Sticking to a traditional performance management process enables bad behaviors like bias to form. In many cases, it also means managers simply don’t flex the muscle of constructive feedback. They may find themselves dancing around subpar performance for the sake of not having an awkward conversation. But in doing so, they sabotage their employee’s ability to improve. They’ve fallen victim to “ruinous empathy”, wherein nobody wins but the status quo of painful performance reviews prevails.

If your organization runs an annual review cycle, then that employee is probably going to be in for a rude shock when that manager is forced to codify a review of their performance. Which takes us back to just how bad these processes make employees feel.

We’ve advocated for a universal language for performance for years, and recently implemented a capability-led approach at Acorn. Using Capabilities, we focus on professional growth as the outcome of any performance conversation. How so?

Capabilities are derived first and foremost from business strategy before being mapped to job roles. That means that every Acornian can trace their personal impact on business through the core capabilities of their role. More than responsibilities, capabilities are key measures of what needs to be done to be successful in any role.

The real juice comes from each capability’s proficiency levels. At Acorn, we use a scale of:

- Foundational

- Developing

- Proficient (the desired level for most capabilities)

- Advanced

- Expert.

Let’s say you have two designers on a design team, one who’s worked at the organization for three years and the other who’s been there about a year and a half. You’re starting to scale and know that you need a senior designer on the team. You could promote by seniority, but that’s not rooted in performance or potential. Likewise, you could 9-box it, but you need the right information to do that accurately.

A capability assessment evaluates employees on their demonstrated performance, by way of proficiency. Say the senior designer role has the capability of user-centered design, with a required proficiency level of advanced. You can assess against said capability to understand the gap between their current proficiency level and the level required for the role.

The ROI of a universal language

The disconnect between employee performance reviews and improved performance comes down to effective feedback—this we know. Thing is, a lack of change in employee performance then makes it hard to show any tangible impact of learning and performance initiatives. Middling employee development programs mean leaders can’t judge performance to begin with. The cycle is vicious, and it goes round and round.

Where capabilities really sing for their supper is in showing business impact. As we said, they are, by nature, strategically aligned. You can show the strength of everything from L&D to talent management plans based on the availability of capabilities in your organization.

There are also a few other advantages.

- Performance data is actually actionable for talent decisions. Promotions are not just fair; time to proficiency is faster and there are fewer hampers to productivity. That informs future succession planning and development plans, and ensures managers are not making biased decisions.

- Team performance is stronger with clear links between the day-to-day and business objectives. Not only can leaders design stronger units and make team objectives clear, but individuals within those teams understand the push and pull of their roles against their teammates. All in all, that equates to a more positive team environment.

- You have mechanisms through which to identify and reward high performers. Oh, and you get to enjoy the flow-on effect of top talent’s job satisfaction: the boost in motivation they get from recognition spills over to the rest of their team, according to the Harvard Business Review. Nothing to sniff at when you consider high performers are usually 400% more productive than the average employee.

- Conversely, underperformers are spotted before they can drag productivity and morale. How so? Acorn’s Capability Gap Analysis Report shows you who’s coming in under their required proficiency level, anywhere in the organization and at any given time.

- Retention goes up with a true culture of career growth. Plus, learning with the goal of career development generally accelerates the flow of critical knowledge and skills within a business, given people are a) speaking the same language and b) driving business performance through individual capabilities.

Key takeaways

High-performing organizations are driven by high-performing people. And high-performing people are driven by opportunities to grow, which can only be uncovered through fruitful performance conversations with managers.

Those conversations require managers to feel confident and be equipped with the right tools to give constructive performance feedback. It’s a two-parter. You need:

- A universal language in capabilities ensures learners and leaders alike understand what is needed to succeed in every role.

- A platform to make capabilities visible and accessible for everyone.

Looking for just that? Check out our Capabilities platform to learn how you can enable your managers to make both your people and organization high-performing.